It helps to have a plan. For business, for life in general, and certainly for growing plants to eat, planning gives you some control of the future. January is planning month for lots of northern gardeners. My planning includes going though several favorite seed catalogs and ordering seeds to replenish any in short supply in my seed inventory.

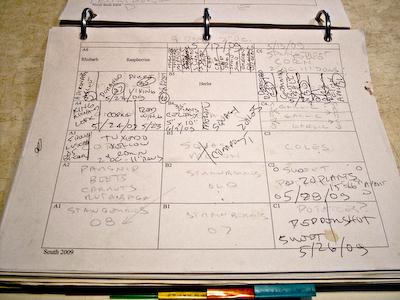

I also start looking at what is going to be planted where. In January, I print out two new charts for my south and north garden beds and start to pencil in the plan of crops and their locations. The charts go back to 1986, but it’s really the last seven years I care about. I use previous years’ charts to help maintain a rotation that I took from Eliot Coleman’s book, The New Organic Grower.

The rotation was designed for a large acre and a half plot designed to feed 40 people, but with a few modifications, I find it works well for me. I also use a rule not to plant the same type crop in a bed without at least a four year break, but I prefer to try to keep seven years between planting a crop type again in the same bed.

Coleman’s rotation is this: Potatoes after sweet corn, corn after cabbage, cabbage after peas, peas after tomatoes, tomatoes after beans, beans after root crops, root crops after squash, and squash after potatoes. I won’t explain Coleman’s rotation logic, it’s in the book, but the benefits of crop rotation are proven, and I’m in total agreement with Coleman’s statement, “. . . crop rotation is the single most important practice in a multiple cropping program.”

Since the rotation doesn’t address lettuces and greens, nor onions, I typically plug those in with root crops, but in trying to fit the puzzle together as I lay things out, I often have to resort to the four year rule when I have an empty bed and something that needs to be planted.

I have a large garden by most backyard standards. With over 20 beds to play with that are typically 5 feet wide by 22 feet long, it’s easier for me to plan a rotation than it would be for someone moving all the possible things they would like to grow through a small 10 by 20 foot space. But the point is that by charting and keeping track of what was where in previous years, a crop rotation can still be achieved.

For the most part, any rotation is better than none, especially if the logic that many similar crops should not be planted directly after each other in the same spot is applied. Crop rotation balances the nutritional needs of the plants and it reduces the buildup of insect and disease problems. It also seems to act as a soil amendment in making hard soils easier to work.

A few snags to an to easy rotation for my beds are strawberries, rhubarb and raspberries, which remain in place up to three years and asparagus, which never gets moved. I’m also now experimenting with letting more greens and herbs go to seed and self sow. If they are in a place that isn’t bothering me, I let them grow where they have volunteered. But I’ll admit that it’s much easier to do rotations in a large garden versus a small one.

As we try to grow our CobraHead tool business, garden planning is taking on additional importance. We now point to our own gardens as part of our how-to program to try to help gardeners grow food. My gardens in Wisconsin and Geoff’s gardens in Austin are now the CobraHead Test Gardens for Northern and Southern Climates. And there is a huge difference in how and when things are done up here and down there. Our Wisconsin gardens are under a foot of snow, while until two weeks ago when a cold snap hit, Geoff was harvesting bountiful crops in Texas.